A Hero On Mount St. Helens: Remembering David Johnston

Dr. David A. Johnston is a person I’ve looked up to for most of my life. I first learned about him when I was a child, reading Marian T. Place’s book about the eruption of Mount St. Helens. He watched an active volcano. He warned a lot of people that she was going to violently erupt. He saved countless lives, but lost his own. He became a personal hero of mine, especially as I grew up and learned more about the work he did and the risks he took.

So I was super excited when I saw a whole book was being published about him. I bought a copy as soon as I could. Then…

I didn’t read it for a year. Because what if it got him wrong? What if it was over-dramatized? It’s by someone who’s neither a geologist nor a science writer – what if she got the volcanology all wrong? What if she didn’t do him justice?

And, also, I have a thing about reading about the deaths of people I really like and respect. I chicken out. (I mean, I didn’t finish a really good biography of Alexander Hamilton because I didn’t want to see him get killed in that bloody awful duel.) So I wasn’t looking forward to that bit.

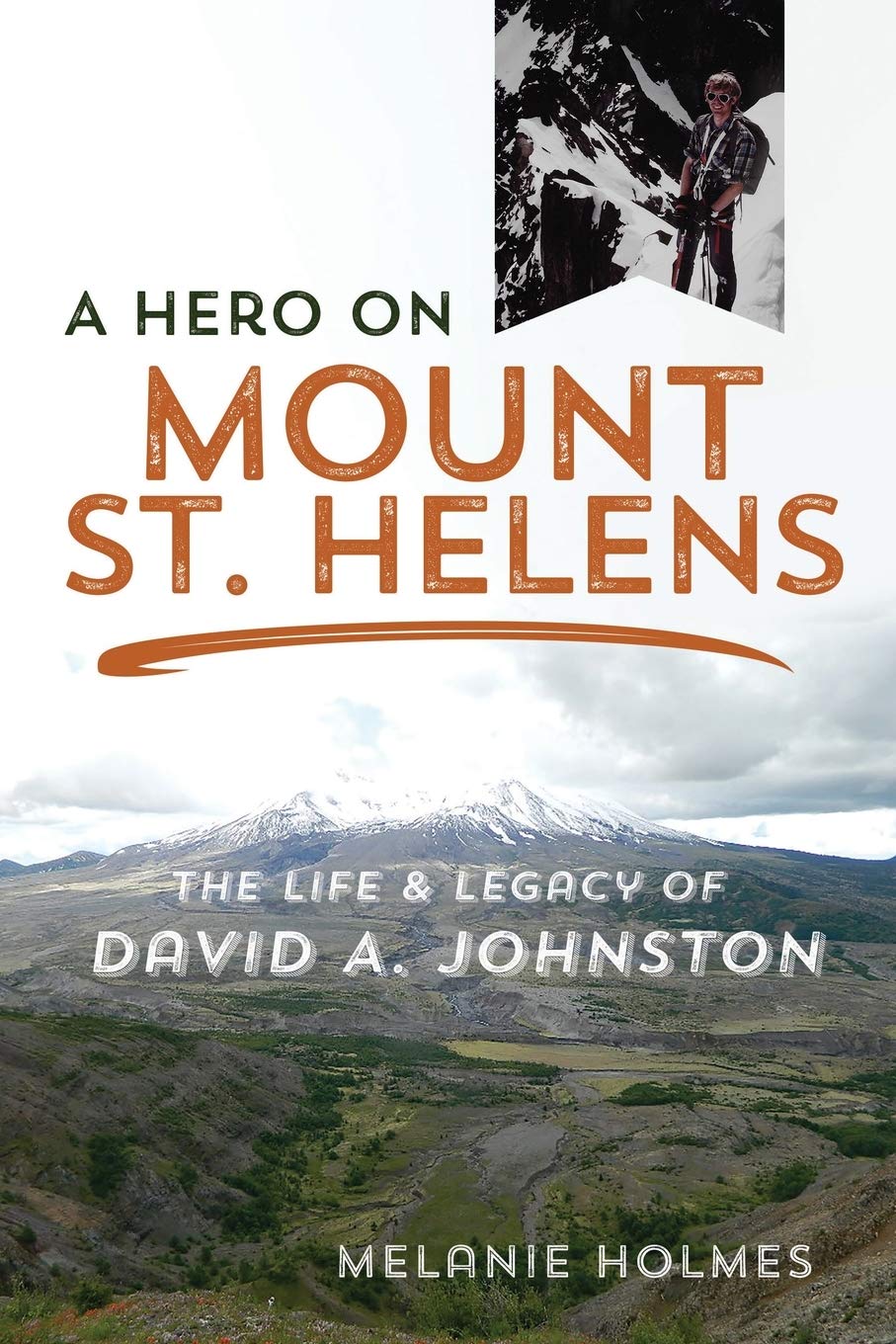

Finally, I screwed my courage to the sticking-place, stocked upon ultrasoft tissues, and picked up Melanie Holmes’s A Hero on Mount St. Helens: The Life and Legacy of David A. Johnston at last.

People, precisely none of my fears came true. Melanie is actually friends with Dave’s sister Pat, and wrote the book at her behest. She researched his life and the eruption in exacting detail. She had several geologists who were with Dave on Mount St. Helens review the manuscript. She toured the Cascades Volcano Observatory. And she absolutely did Dave justice.

Dave Johnston with a monitoring device at Mount St. Helens, 1980. Credit: USGS

In this book, we learn that Nature had it out for Dave for a long time. He came within a whisker of being murdered by a tornado in his teens. Augustine Volcano came thisclose to claiming his life in his twenties. I don’t actually believe in fate or predestination or that Mother Nature can commit premeditated murder, but the events of Dave’s short life sure wouldn’t disprove the idea.

He was going to follow his mom, Alice, into the newspaper business, and was already making strides as a photojournalist when geology turned his head in college. It was a much better fit for him: he got to be outdoors, and he didn’t have to invade people’s space with a camera.

Those of us who didn’t personally know Dave will be surprised by the person Melanie introduces us to. He seemed so confident and rugged on Mount St. Helens, giving interviews to the media and going down into the crater to retrieve samples despite the incredible danger. We see him with his beard and his plaid, and we don’t think of a person with frailties and insecurities.

The most valuable thing about this book is how it shows us a complete human being. Dave was a small kid who was painfully aware of his lack of brawn. He was continually pushing himself to be better physically, even though he was objectively fine as he was. He fought anxiety throughout his life. He beat himself up over imperfections. He was painfully shy, to the point that he would sometimes pass out when giving presentations – even fainting multiple times during a Geological Society of America talk. He wasn’t tough and fearless and immediately good at everything he did.

Melanie presents those aspects of him with great empathy. She shows how he overcame those obstacles to become a well-respected volcanologist by his late twenties. She shows how he used determination, ingenuity, a dinosaur toy,* and humor to compensate, and how his friends and colleagues accepted him, vasovagal syncopes and all. And she shows how he often didn’t succeed despite his perceived weaknesses, but because of them. It’s a refreshing change from biographies that make their subjects look almost superhuman by papering over any flaws. It reminds us that we can have all sorts of illnesses and limitations and insecurities, and still be fantastic at difficult jobs.

We get to see Dave’s career take off at the USGS, and then comes Mount St. Helens’s awakening. He’s worked on a dangerous active volcano. He knows how deadly Mount St. Helens could be. His healthy fear of her power saves countless lives. He personally sends people out of the danger zone. He stays behind because he knows his work there is critically important.

He recognized the similarities Mount St. Helens had to Russia’s Bezymianny. He was one of the first to recognize that, like Bezy, she might blow laterally. He knew the risks. And he didn’t want to die. But he did his job.

One of his last acts was to save the lives of two young USGS geologists who had planned to camp out near Coldwater II on the night of May 17th, but Dave told them it wasn’t safe and talked them into returning to town. The women joined Dave and his graduate student assistant Harry Glicken on the ridge for a while before heading back. Dave’s last night on earth was filled with camaraderie and laughter. At the end of it, he waved goodbye, and returned to monitoring the volcano for the last time.

Dave writing up notes while visiting with other geologists on the last night of his life. Credit: Harry Glicken/USGS

One of Dave’s last exchanges with his colleagues was a quip. Asked about the SO2 readings early on the morning of May 18th, Dave said there wasn’t any detected, but there was an internal build-up of H2S. He’d probably find it hilarious that possibly his last joke on earth was a fart joke.

And then, too soon, there’s the eruption. I was terrified to reach this point, but Melanie handles it beautifully. She uses a crisp, almost clinical brevity to narrate the events of that day. She handles the horror of losing a beloved son, brother, and colleague with grace and empathy. We’re not spared detail, but she doesn’t deliver the sensationalism that too many other authors have.

The rest of the book details Dave’s legacy. We see how much impact his short life had on volcano science. We see the memorials to him, and to other victims of the volcano. And the ending strikes a pitch-perfect note.

I can’t think of a better tribute to Dave’s life and work. There’s literally only one caveat I have about this book: the print is pretty tiny, so if small type bothers you, get the ebook version instead of the paperback. Otherwise, this is a necessary book for anyone who wants to know more about Dave Johnston, Mount St. Helens, and volcanology. Just. Make sure you have tissues, because there are a few places that are going to hit you right in the feels. And that’s just as it should be.

A Hero on Mount St. Helens: The Life and Legacy of David A. Johnston by Melanie Holmes

* I have a feeling Dave would thoroughly enjoy this modern version of his spark-spewing dinosaur toy. If I ever give another geology talk, I’m bringing this guy.

Rosetta Stones and Dana Hunter’s Unconformity wouldn’t be possible without you! If you like my content, there are many ways to show your support.

This website is a member of the Amazon Affiliates program. I get a small commission when you use my affiliate link to make a purchase.

Thank you so much for your support!