Category: Natural Disasters

42 for Loowit’s 42nd vol. 7: Reprise

There was life in the old girl yet.

To be fair, though, Loowit (Mount St. Helens) isn’t very old as far as volcanoes go. So when she rumbled awake in late September of 2004, volcanologists weren’t terribly surprised. She’d slumbered for less than 20 years after her 80s eruptive sequence, but it wasn’t shocking to see magma on the move again.

Her prompt eruption on October 1st signalled a new phase of dome building. And this time, we had better cameras, better monitoring equipment, and the plans in place to do some serious monitoring.

Dome within Mount St. Helens’ crater is hot and glowing as it grows, viewed from Johnston Ridge Observatory (JRO), with base of small steam and ash plume. 11/4/2004. Caption and image credit: USGS

She put on a beautiful show. (more…)

42 for Loowit’s 42nd vol. 5: Cataclysm

It’s a beautiful, quiet morning with spectacular weather, and then suddenly it isn’t. An earthquake strikes, the bulge gives way, and the volcano blows up and out.

Mount St. Helens in eruption. Aerial view of base of eruptive column, crater rim at right. Shows “cauliflower” effect in column. 1235 hrs PDT. Skamania County, Washington. May 18, 1980. Caption and image credit: USGS

This actually isn’t a particularly large eruption. Between the lateral blast, Plinian ash column, and the pyroclastic flows, it totals only about 1.4 cubic kilometers of material. Barely a VEI of 5. But if you’re in it, it seems large enough to have swallowed the world. It is, indeed, cataclysmic.

42 for Loowit’s 42nd vol. 4: Menacing May

May had begun with an ominous quiet.

Ominous? Surely a restless volcano quieting down is a good thing!

Yeah, not when you’ve got one flank of the mountain growing a bulge like a demonic pregnancy and displaying worrying new thermal anomalies. Add in earthquakes and dramatic swelling, and you’re sure the volcano is ready to pop.

Geodimeter station at Toutle Canyon near Mount St. Helens. Skamania County, Washington. May 2, 1980. Caption and image credit: USGS

[Monty Python voice] Look at the bulge! (more…)

42 for Loowit’s 42nd vol. 3: Ominous April

For the people who lived and worked on the flanks of Loowit (Mount St. Helens), her awakening was both curse and blessing. Living with a restless stratovolcano isn’t safe nor comfortable. But the tourism it draws is great for the local economy. Locals leaned in, creating funny hats and shirts, renaming menu items, and finding other creative ways to capitalize on her activity.

For the scientists who flocked to her, it was the chance of a lifetime.

Aerial view of Mount St. Helens and drifting plume, from northwest. Photo taken from U.S. Forest Service observer plane at 12:32 p.m. Skamania County, Washington. April 4, 1980. Caption and image credit: USGS

Volcanologists flocked to her slopes, installing equipment, taking measurements and photos, and flying over the summit as steam and ash spurted into the sky. They’d seldom had a chance to study an actively erupting composite cone so conveniently close to highways and large cities. Loowit was wonderfully accessible, and easy to observe, even in the Pacific Northwest’s capricious early spring weather. (more…)

42 For Loowit’s 42nd vol. 2: March Awakening

There’s this old saying about March: “In like a lamb, out like a lion.” This turned out to be very true in Loowit’s case as the 1980s began.

After over a century of peaceful slumber, Loowit (Mount St. Helens) began to wake. Seismic activity is nothing new around volcanoes, but this swarm was intense enough to shake the snow from her summit.

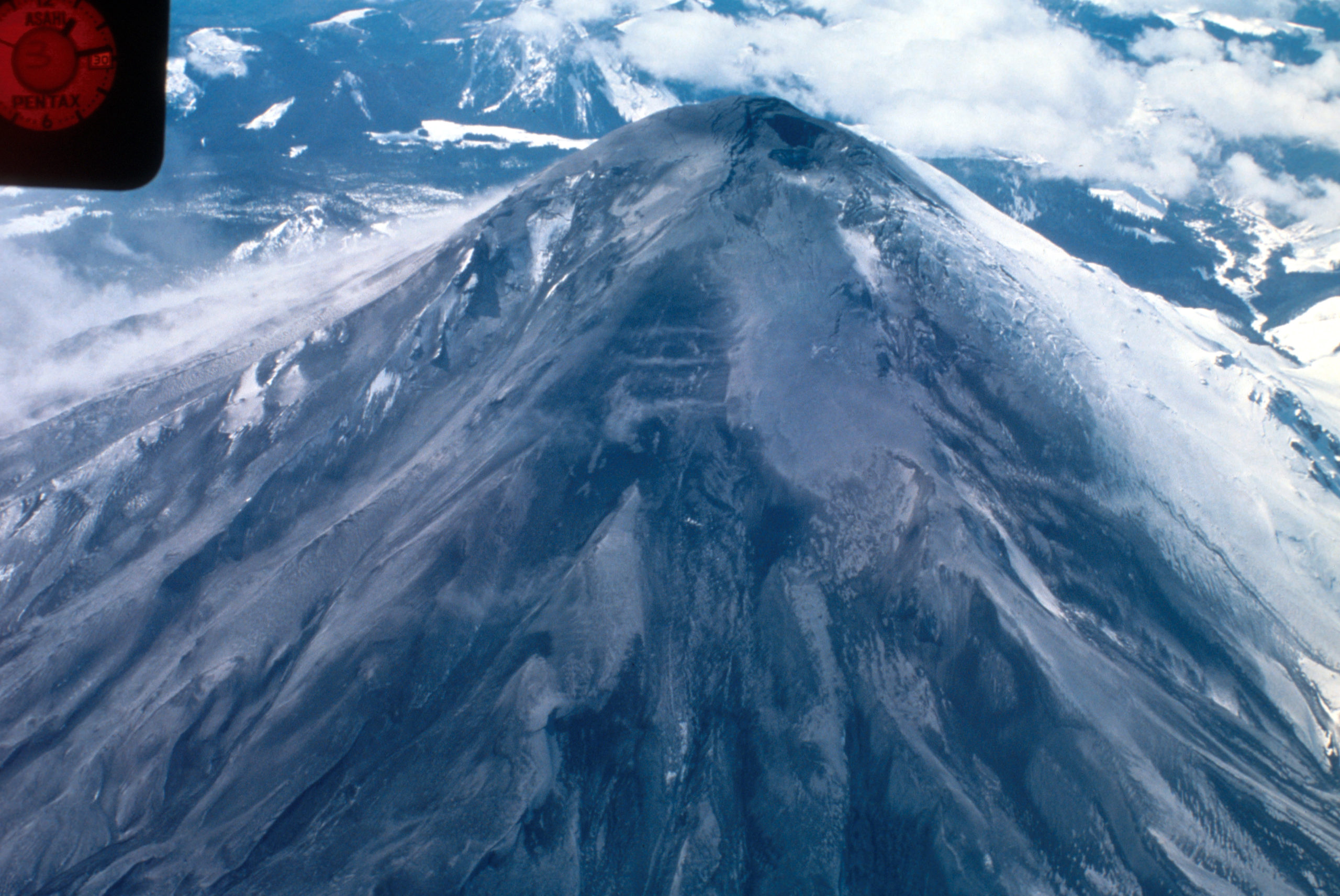

North side of Mount St. Helens, Washington, as of 24 March 1980. Numerous snow avalanche fracture scarps may be related to continued earthquake shaking. No signs of volcanic activity are evident. Caption and image credit: USGS

She still looked lovely and serene, but as March waned, signs became increasingly clear that magma was on the move in a serious way. (more…)

42 for Loowit’s 42nd vol. 1: Pre-1980 Majesty

What’s the answer to life, the Universe, and how many years it’s been since Loowit (Mount St. Helens) erupted? Why, 42, of course! We’ve plundered the archives of the United States Geological Survey and the US Forest Service for 42 of the best historical photos, plus bonus featured images.

Grab your towels and join me on an epic journey back to the 20th Century, in those years when plate tectonics was still in its infancy, volcanology was still young, and Loowit had yet to stir.

Why La Palma is Like This vol. I: The Seamount that Soared

This post first appeared on Patreon. To get early access, plus exclusive extras, please visit my Patreon page.

Now that we’ve got the geologic context of the Canary Islands as a whole figured out, it’s time to zero in on La Palma. How did she get here? Why are all the recent eruptions happening only on one half of her? What might be in store for the future? Does the fact that the most recent eruption is the longest and most voluminous of her entire recorded history mean the island is doomed? And is her active volcanic ridge, Cumbre Vieja, going to fall into the ocean and wipe out the East Coast of North America?

(I won’t keep you in suspense on that last one: the answer is almost certainly a resounding no. So while we’ll talk a bit about former collapses that have shaped the island, we won’t be spending any time on the megatsunami theory. Sorry not sorry.)

A Brief History of La Palma

La Palma is the second-youngest Canary island, and is still growing. She is, in fact, the most vigorously volcanic of the Canary Islands, boasting the most eruptions on record since the Spanish settlers arrived. And that’s just the last 500-ish years of her history: she’s actually about four million years old, if you count from her birth as a bouncing baby seamount. Nearly all of those years involve very hot rocks. (more…)

The Blanco Fault Zone Rides Again

Do we have to do this again so soon? Really? Oh, geez.

Must we really, CNN? Credit: Dana Hunter

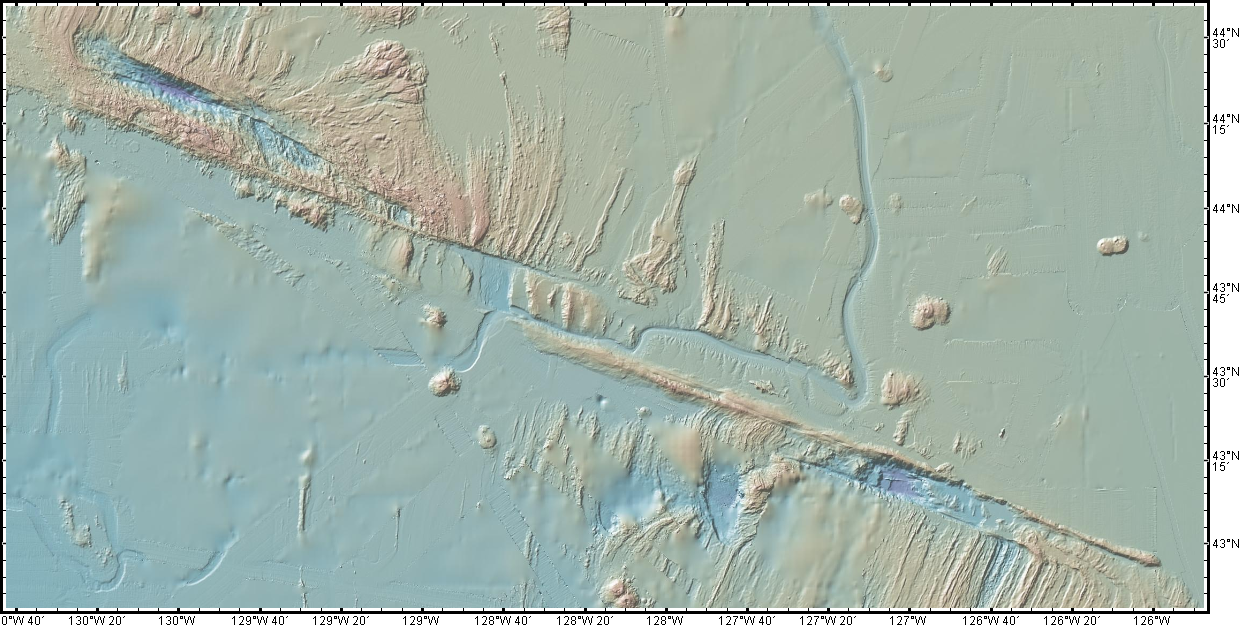

I’m not going to link that article, because while it does quote seismologist Harold Tobin up front basically saying nothing to see here, folks, everything’s normal on the Blanco Fault Zone, it also tries to scaremonger. And I’m so over the scaremongering.

Listen. This is the Blanco Fault Zone. Earthquake swarms with many temblors of this magnitude are its specialty. It means absolutely nothing for the mainland. Zip. Zilch. Nada. Read this very good article on Oregon Public Broadcasting, which laid out the facts in beautiful form.

And no, this has utterly nothing to do with submarine volcanoes. No, not even Axial seamount. Dr. Jackie Caplan-Auerbach wrote an entire post explaining how much it’s not that:

There have been a lot of questions about the recent Blanco tranform activity, including whether these are related to volcanic activity in general, and Axial Seamount in specific. The short answer is no, these are definitively not volcanic quakes, but more detail follows.

First, the Blanco Transform fault is the most active fault in the Pacific NW, with very frequent quakes >M5. We can tell that these are normal Blanco faults by their location, by the way they fail (these are strike-slip earthquakes, consistent with the fault’s normal behavior, and happily, the type least likely to generate tsunamis).There is no volcanism associated with transform faults. The nearest frequently active volcano (and the one people most often ask about) is Axial seamount, which is ~300 km from the activity we are seeing on the Blanco this week. This is much too far apart for these features to be associated with one another.

And I swear we all have to do this every dang time.

For anyone who’s been worried that this is the harbinger of something geologically awful in the Pacific Northwest, please be assured that it is not. This is absolutely business as usual on the Blanco Fault Zone. This is what it does. It’s not going to trigger the Cascadia megatsunami. It’s not even going to cause any minor inconveniences to the mainland. Volcanoes aren’t going to be triggered. Literally the only way it’s going to become an issue is if we decide to build a seafloor city right on top of it. Which, knowing humans, someday we will definitely do.

Just a hair over two years ago, my Scientific American article explained why the Blanco should be considered a fun rather than fearsome fault zone. I shall now reproduce that article here, because literally nothing has changed except the date. Please bookmark this to reference whenever someone starts freaking out over the Blanco’s latest antics. It’s all chill, folks. Just enjoy it’s little productions! Because they’re actually entertaining and informative from an earth science perspective, just the way we like our geology. (more…)

A Kilauea Thanksgiving

Hello, my lovely people! It’s American Thanksgiving, and hopefully most of us subject to it have survived without too many kitchen mishaps and family feuds. If you’ve spent it alone, I hope you’ve had a lovely bit of solitude. And for those of you who, like me, worked the day, I hope everything went as smoothly as a holiday can.

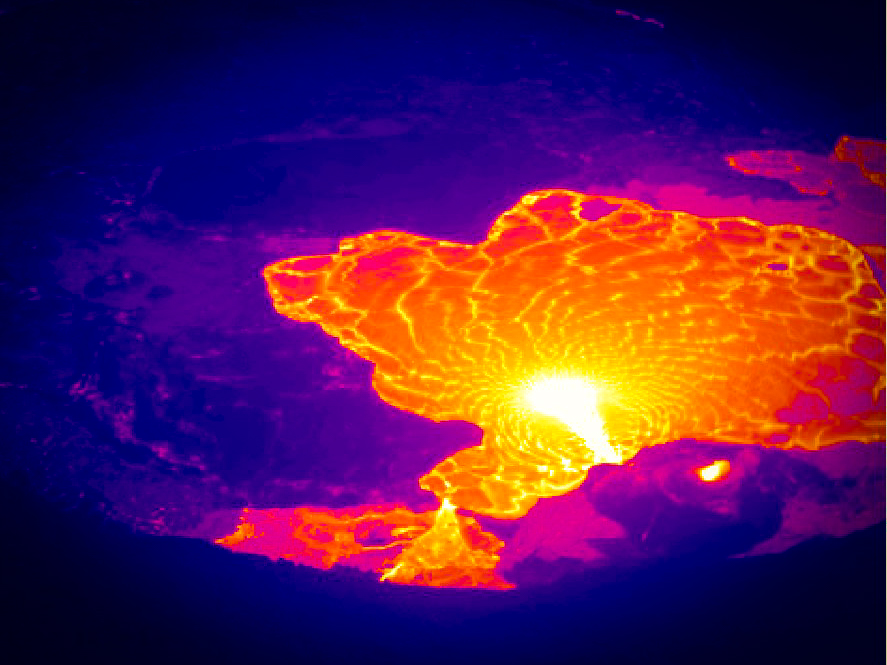

Let us give thanks to Tūtū Pele, who has provided us with this lovely and relatively safe ongoing eruption in her home on Kilauea volcano:

A few days ago, I noticed a fairly large although fleeting increase in the output of lava from the summit vent. According to the USGS, it lasted just a few hours, and then all went back to the current normal. But it sure did look neat in the summit webcams! I grabbed the relevant bits and slowed them down for you.

Here ’tis in the thermal cam: (more…)

Why the Canary Islands are Like This

This post first appeared on Patreon. To get early access, plus exclusive extras, please visit my Patreon page.

The current eruption on La Palma in the Canary Islands is now over a month old. Already the island’s largest in a hundred years, it’s giving no signs of stopping just yet. Volcano lovers have thrilled to its spectacular Strombolian explosions. Residents have endured disruption, displacement, and loss of homes and livelihoods. Dogs trapped by lava flows had to be fed by drone before they were taken to safety in a daring and mysterious rescue. Living with a live volcano is far from easy and seldom safe.

Plenty of news agencies, vloggers, and blogs are keeping us up to date on the progress of the current eruption. I’m going to take us deep into the past, on a journey into the island’s origins and evolution. We’re going to see the slow, steady pas de deux between a mantle plume and the plate above it. We’ll watch underwater volcanoes go subaerial, building new land, and see catastrophic collapses tear their confections down. We’ll learn the life stages of a Canary Island, and by the end, we’ll know the broad outlines of La Palma’s destiny.

In the end, we’ll see that this current eruption is as much an act of creation as it is destruction.

Mirador de La Tarta, Tenerife. Yes, it’s literally called a cake! The white layer is pumice, the black layers are basaltic scoria, and the reddish-brown layers are oxidized basaltic tephra. Credit: H. Zell (CC BY-SA 3.0)